What a Spitfire Pilot Can Teach Business Leaders Today

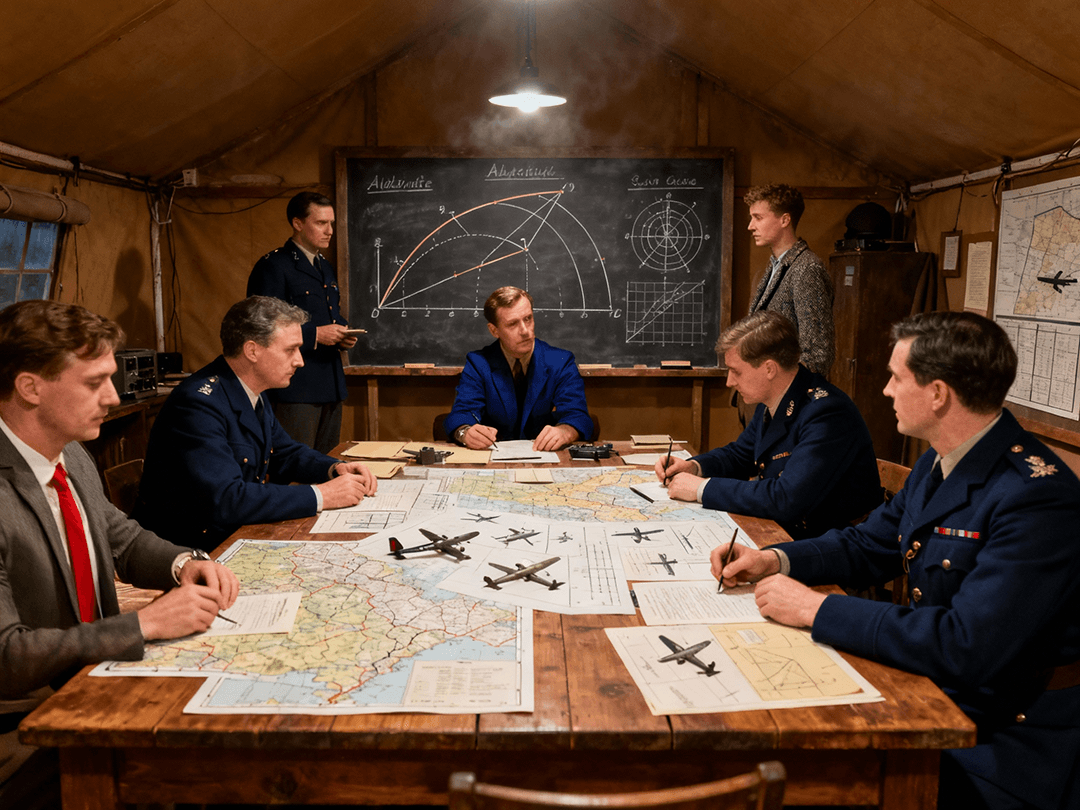

An exploration of Professor Peter Checkland’s Soft Systems

If you walked into a bookshop today and picked up a glossy volume about wartime heroes, you’d probably expect tales of pilots looping through flak-filled skies, engines screaming, and impossible odds defied. But every so often, history gives us a story that doesn’t just replay old heroics. It hands us something stranger, sharper, and far more useful than nostalgia.

Flight Lieutenant James Brindley Nicholson offers one of those stories.

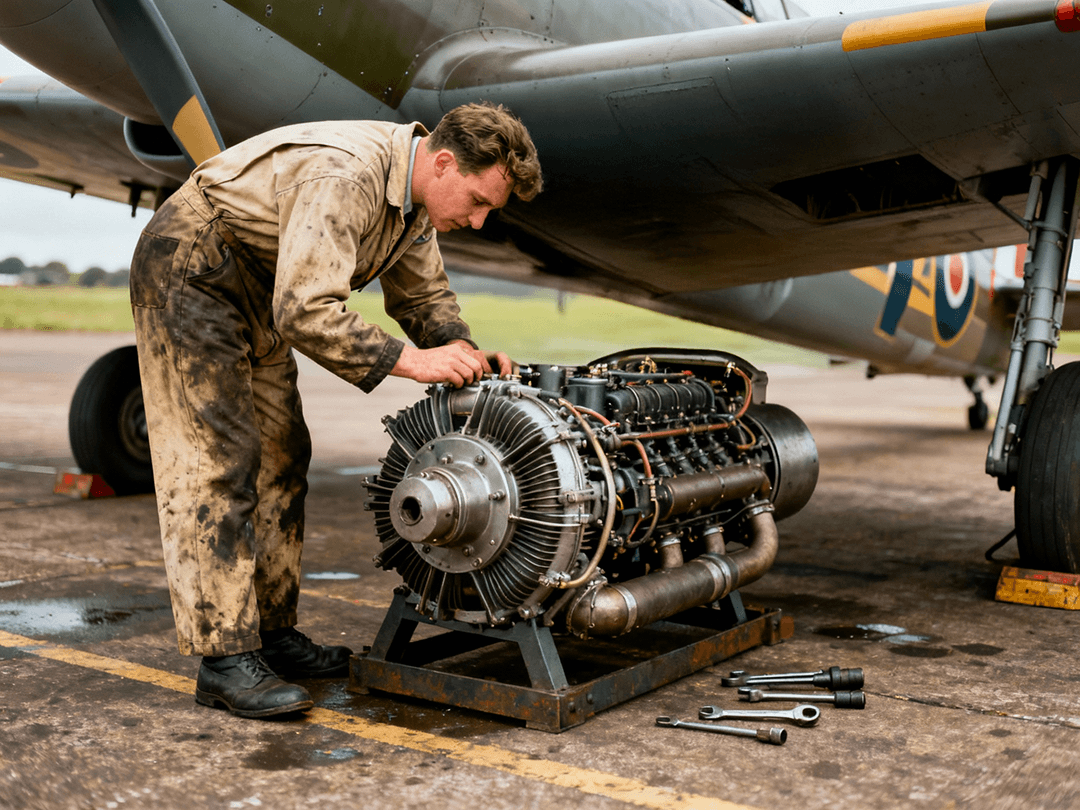

Nicholson isn’t the first name most people associate with the Battle of Britain. Yet his September 1942 engagement over the Sussex coast stands as one of the most extraordinary individual actions in the entire air war. His Spitfire was leaking coolant, hydraulics were failing, the engine was cooking itself alive, and the Luftwaffe held all the tactical cards. Any normal pilot would have turned for home and prayed the Merlin engine didn’t seize over the Channel.

Nicholson didn’t.

He climbed directly towards the enemy.

His decision broke every rule in the book. And because the Luftwaffe relied on those rules, his unexpected move shattered their formation, scattered their coordination, and turned a damaged aircraft into a weapon more dangerous than a healthy one. The RAF studied his engagement for years, not simply because he survived, but because he revealed something doctrine could not explain.

Nicholson showed that systems built on predictable rules collapse the moment a human refuses to behave predictably.

That realisation connects directly to the work of another Englishman: Professor Peter Checkland, the Oxford-trained chemist turned management scientist whose “Soft Systems Methodology” reshaped how we understand organisations.

Machines Obey Rules. People Interpret Them.

Professor Checkland observed that most organisations treat human work like engineering inputs, outputs, flowcharts, and rigid processes. Useful, yes, but dangerously incomplete. Unlike engines or hydraulic pumps, people bring meaning, emotion, and interpretation into every situation.

Checkland called these messy, meaning-laden situations human activity systems.

In “hard” systems thinking, problems behave like broken machines. Fix the part, tighten the screw, feed the process, and the outcome improves.

But in a “soft” system, the problem isn’t the machine.

It’s the multiple worldviews interacting inside it.

Different people seeing the same situation differently.

Different incentives.

Different interpretations of what “success” even means.

Nicholson understood both sides of this divide long before management books existed. German pilots expected a damaged Spitfire to run. RAF doctrine expected a pilot to preserve the aircraft. Engineers expected the Merlin engine to be treated gently once coolant pressure dropped.

Nicholson rejected all three expectations at once. He didn’t see a checklist. He saw a field of relationships, enemy assumptions, aircraft tolerances, environmental conditions, and his own intention. He didn’t follow the system. He reframed it.

And that’s the exact moment where Checkland would say:

“You’ve stopped treating this as a mechanical problem. You’re interpreting the situation as a human one.”

What This Means for Today’s Business Leaders

Leaders often assume their organisations behave like aircraft engines. They optimise, measure, control, regulate. But most failures inside modern companies have nothing to do with faulty processes. They arise from misaligned assumptions, conflicting meanings, and people working from different stories about what the organisation exists to do.

When a team behaves strangely, or a competitor acts unpredictably, or a project spirals despite flawless planning, the problem usually isn’t mechanical.

It’s human.

Checkland’s Soft Systems Methodology teaches leaders to slow down, map the different worldviews at play, understand the purposeful actions of each stakeholder, and treat the organisation not as a machine but as a living network of interpretations.

And Nicholson’s engagement shows the cost of ignoring those interpretations. German pilots, confident in their data and doctrine, misread the situation because they assumed the British pilot shared their priorities. They assumed symmetry of intention.

They assumed the world would behave according to their model.

It didn’t.

Why Some Models Capture More Than Procedures Ever Can

Some leaders use an additional framework for understanding situations that behave more like living fields than machinery. This kind of model looks at the organisation as an interconnected landscape where intentions ripple, meanings collide, and decisions create patterns that pull events into coherence. Instead of seeing people as cogs, this approach views them as sources of resonance, each interpreting reality through a different lens.

When those lenses align, systems behave smoothly. When they diverge, unpredictable outcomes emerge, just as they did in the Sussex sky.

This field-based way of seeing helps explain why an outlier like Nicholson can transform a situation that seemed mathematically unwinnable. He acted as a singular point of coherence inside a chaotic environment. His interpretation, not the machine’s limitations, defined the path ahead.

In the End, It’s All About How You See the Situation

James Nicholson survived because he understood his aircraft at a technical level, the enemy at a psychological level, and the situation at a human level. Professor Peter Checkland spent his academic life teaching organisations that same principle in calmer circumstances.

Mechanical thinking explains how systems function.

Soft Systems thinking explains how people behave.

And the greatest advantage belongs to leaders who understand both.

Download the full paper here.

© 2025 Stephen Bray. Patterns in life and business, simply told.