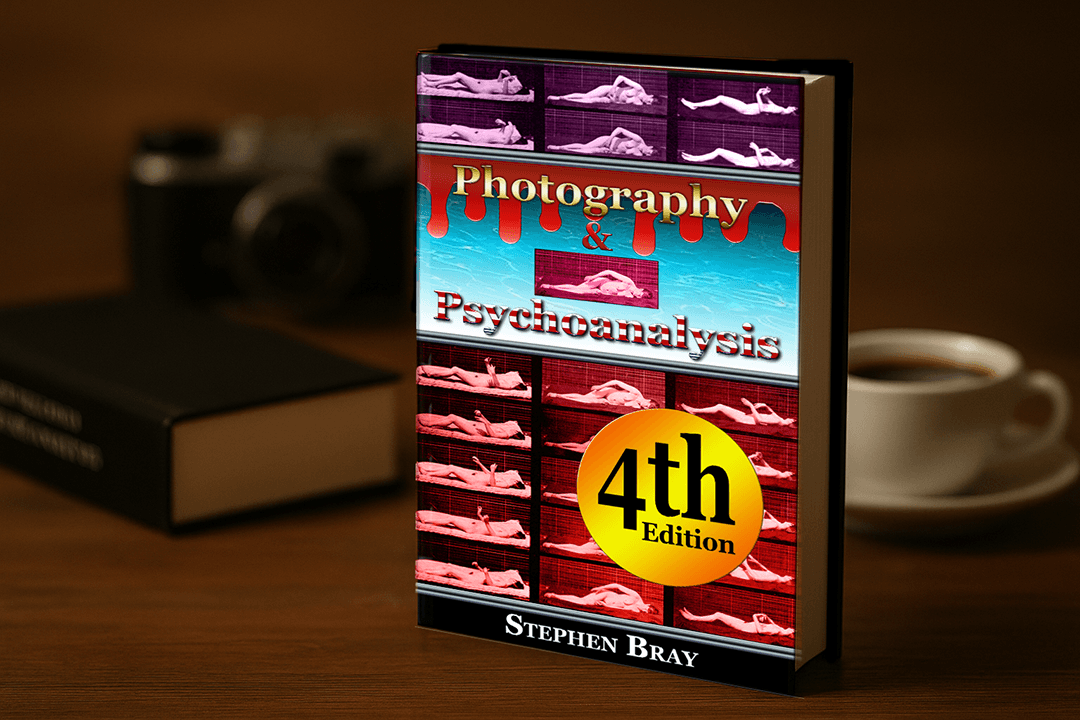

PHOTOGRAPHY & PSYCHOANALYSIS

The Development of Emotional

Persuasion in Image Making

This concise, illustrated, work informs about the histories of photography and psychoanalysis. It describes how they came together in the 20th Century to revolutionize political propaganda and sales messages. It references the works of several 20th Century and contemporary photographers including: Edward Steichen, Brian Duffy, Helmut Newton, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Nan Goldin, Gregory Crewdson, Larry Clark, and Wang Qingsong.

Now in its fourth edition it summarizes and critiques many of the thoughts of the philosopher and activist Susan Sontag. It also analyses the photographic basis in the Works of Andy Warhol, and why his artwork is important to photographers, and those wishing to understand commercial propoganda.

It demonstrates how images may be understood, and interpreted, using the ideas of Freud, Jung and Lacan.

This is your chance to understand, and free your mind from, assaults by those images which, every day, make you feel less, and less, happy, unless you buy, buy, buy.

Inside The Book

His Hands Fumbled And Our World Changed.

NICÉPHORE NIÉPCE (1765 to 1833) had a problem. He trembled. It was neither ‘the shakes’, nor Parkinson's disease that ailed him, but simply that when he attempted to trace the outlines projected into his camera obscura his hand shook and the results were abysmal.

Niépce had an inventive mind. He saw at once that were it possible to remove himself, and his shaky hands, from the engraving process, his work would be better received.

He set about devising a means to fix the image projected within his camera obscura on various media. His first success was to create an image on pewter using a solution of bitumen dissolved in lavender oil (a traditional solvent used in artists pigment). After an eight-hour exposure, he was able to rinse the bitumen layer from the pewter and reveal an impression of the rooftops beyond his studio window.

The image is not as unremarkable as one might expect of a monochrome picture of suburban rooftops. Two thirds of the image is taken up with buildings, but one area is a clear sky. The long exposure, however, produced an incredible effect. Shadows appear on both sides of the buildings. How blessed Niépce must have felt on that day when he first saw it!

What is common to Vermeer, Spinoza and Niépce is their need to understand and harness the power of light. The very concept of light is itself a powerful metaphor for consciousness. The unconscious has always been associated with darkness, reflections, moonlight, or water.

Hitler's vision was very different. For Fascism to succeed he needed to harness unseen powers within darkness.

It doesn't matter if we believe, like Descartes, that body and spirit are divisible, or like Baruch Spinoza that all are one, what we see in Cameron's images is an attempt to reflect 'some essential truth' about her subjects. There is no flattery, nor are any artificial props added, as in Vermeer's paintings.

But, what is 'truth'?

William James held: "The truth of an idea is not a stagnant property inherent in it. Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events. Its verity is in fact an event, a process: the process namely of its verifying itself, its verification. Its validity is the process of its validation."

Cameron's pictures may seem to show us something of the personalities of her subjects, but in the pragmatic world of William James they too are simply adding validity to our own ideas about her sitters.

If Julia Cameron was producing photographs as evidence of sitters’ personal characteristics, others were putting photography to different uses.

In 1855 Roger Fenton (1819 to 1869) went to the Crimean War as the first official war photographer.

He had the endorsement of the Duke of Newcastle, secretary of state for war, and the patronage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. His images carefully avoided pictures of death and mutilation, and due to the lengthy exposures necessary for the Wet Collodion Process most of his pictures were either posed groups, or landscapes. One picture remains controversial - "The Valley of Death", where the Light Brigade was supposedly wiped out under a battery of Russian cannon.

The true site of the famous charge is several miles to the north-west. It also seems that Fenton may have been unhappy with his original photograph, which shows a road in a winding hollow, and nothing else. In the second picture, taken from the same vantage point, cannon balls are arranged, and add interest, to an otherwise dull landscape.

In America, Captain Andrew J. Russell (1829 – 1902) had no such scruples about photographing the dead, and mutilated. His image following the Battle of Chancellorsville shows where the 6th Maine Infantry penetrated the Confederate lines in May, 1863. Gruesome evidence of life and death struggles are recorded on his plates.

The 'War between the States' is the point at which photography begins to supersede engraved illustration in newsprint.

It was perhaps then that an impression formed that the camera was beyond reproach because it recorded the world objectively.

It's true that sometimes a camera may be used for objective forensic documentation, as in the case of Gordon, a slave who was severely whipped and later served with Union forces in the Civil War. (This is not the only image of Gordon. He also appeared in Harper's Weekly issues, (July 4, 1863 and July 2, 1864), this time as woodcuts, depicting him as both a slave and a private in the Union army).

Our topic, however, is photography and psychoanalysis so this section closes with an image of a patient treated for hysteria by Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot, (1825 – 1893). He was a French neurologist, whose works also influenced psychology.

Charcot identified a number of conditions including 'sclerose en plaques', (Multiple Sclerosis). Charcot must have been an innovative character. He encouraged his pupils, and sometimes patients to draw. He experimented with hypnotism, and later abandoned it, as a treatment for various conditions.

Charcot was one of the first physicians to incorporate photography into the study of neurological cases.

He argued vehemently against the widespread medical and popular prejudice that hysteria is rarely found in men.

His most famous student Sigmund Freud held a different opinion. People erroneously assume that knowing Freud they know Charcot. This is a mistake.

The student may have eclipsed the master in the public imagination, but Charcot was far from being an average physician.

In this section, we looked at the historical roots of photography and discovered that from the very beginning images were open to manipulation, although frequently they are presented as objective documents.

We find people such as Julia Cameron, Captain Andrew Russell and Jean-Martin Charcot attempting to 'keep faith' with the medium and make, what they consider to be objective recordings. Others, such as Roger Fenton would exploit the possibility or arrange the content of their images to add variety and interest to their pictures.

People with no technical training made incredible 'mistakes' which resulted in a lack of formal poses, blurred images, and in general more dynamic content than the 'perfect' images marketed by studio photographers.

The invention of the Kodak® was an event that had been patiently waiting for more than 2000 years.

The Chinese philosopher Mozi (470 BC to 391 BC), and the Greek mathematicians Aristotle (384 BC to 322 BC), and Euclid (300 BC), all described pinhole cameras. But, it was Plato (423 BC to 348 BC) who first used a photographic concept to describe a psychological idea in his 'Allegory of the Cave'.

People watch shadows projected on a wall by things passing in front of a fire behind them. In time they give names to these shadows.

The shadows are the only way in which the prisoners can understand reality.

According to Plato, a philosopher is a prisoner who has escaped from the cave and so is able to see that shadows on a wall are not reality at all.

Had he written his allegory today no doubt he would say that most humans are like workers in cubicle offices who are only able to experience life via images projected onto our computer screens, or mobile tablet devices.

Photographers on the other hand are similar to philosophers, who are able to go out and explore the world. We attempt to capture its essence with our cameras in the hope that the images we make will be able to liberate others from their cubicle prisons.

In fact, Plato is not so far off the mark.

Contemporary science tells us that light leaves the sun, and eight minutes later, it arrives in your environment where some rays of the spectrum are absorbed by the objects that surround you before bouncing through the lens of your eyeball onto the eye's light sensitive receptor, the retina.

It is not just the eyes that see, or at least not entirely. The assembly of your world takes place in the brain. To do so three important stages must take place.

Firstly, all the information captured on the retina is transmitted into the network of your brain cells.

The retina itself is a filter because it cannot sense all bands of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Secondly, that information splits into several channels and gets sorted according to a number of variables, which are prioritized.

High priorities are survival, reflex, habit, and social skill sets.

Thirdly, a fraction of those priorities appears as your awareness, which is the plane upon which you experience your life, (your conscious mind).

It follows then, that we are prisoners of a sort, because we may only be aware of a fraction of whatever occurs around us from moment to moment.

Freud, like Plato, sensed something of our condition. In his book, Studies in Hysteria, he writes:

"Much will be gained if we succeed in transforming your hysterical misery into common unhappiness. With a mental life that has been restored to health, you will be better armed against that unhappiness."

In order to accomplish his aim of enabling people to cope with the challenges of everyday life Freud sought to help them re-order the priorities by which their minds brings raw perception, and memories, into conscious awareness.

In 1900, he treated 'Dora' who was 18 years of age. She had lost her voice and Freud was able help her restore it through the interpretation of her dreams.

André Tridon author of "Psychoanalysis, its History, Theory and Practice", in the foreword of Freud's own work: 'Dream Psychology : Psychoanalysis For Beginners' writes:

"We must follow Freud through the thickets of the unconscious, through the land which had never been charted because academic philosophers, following the line of least effort, had decided 'a priori' that it could not be charted.

"Ancient geographers, when exhausting their store of information about distant lands, yielded to an unscientific craving for romance and, without any evidence to support their day dreams, filled the blank spaces left on their maps by unexplored tracts with amusing inserts such as 'Here there are lions'."

"Thanks to Freud's interpretation of dreams the "royal road" into the unconscious is now open to all explorers. They shall not find lions, they shall find man himself, and the record of all his life and of his struggle with reality."

Dreams, according to Freudians, are the means by which we may enter into the place where our minds sort and prioritize the data we receive via the five senses. This prioritization gives rise to our experience and responses to it.

In the next chapter, you will learn the ways in which Freud understood the mind to prioritize information, and how this relates to photography.

Why I Wrote This Book

Photography and Psychoanalysis marked my first serious book project after years of shorter-form work in newspapers, journals, and even a glossary of NLP terms. The research revealed a clear harmonic gap, the near-erasure of Black and other ethnic photographers from the historical record, despite their decisive influence on the medium.

I also saw how both photography and psychoanalysis can drift from their original resonance when pulled by commercial agendas, yet still produce moments of extraordinary coherence. Some of the most inventive work came from artists embedded within those very systems.

This book grew from the act of listening for the pattern beneath the noise, holding each contradiction until its deeper structure revealed itself.

If you've ever wondered why people but so much junk, then you need to read this book.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.